The Extent of Government Support for Frontline Workers in Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan During the Pandemic

8 April 2021

During the COVID-19 pandemic, key nutrition and health Frontline Workers (Anganwadi Workers, ASHAs, and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives) found themselves with new roles and responsibilities in addition to their regular tasks (read our previous blog). This meant that they required new means to perform – primarily training on COVID-19 related activities, and resources from the government.

In November 2020 and January 2021, we studied the experiences of the Frontline Workers (FLWs) in two districts of Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan (download this report to access complete findings from the quantitative and qualitative study). We discuss some findings in this blog.

FLWs felt adequate training was provided for most activities

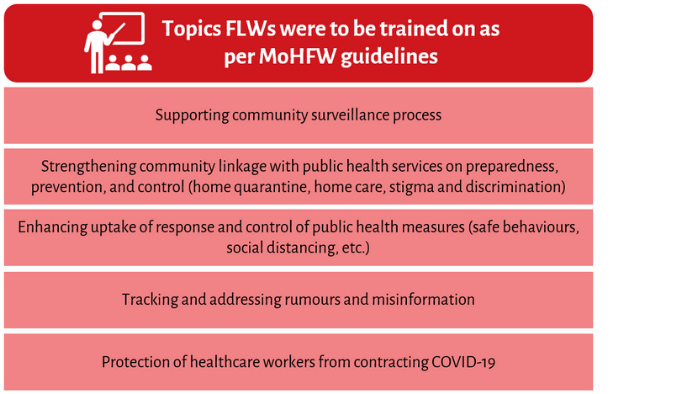

Given that FLWs are the first point of contact rural citizens have with the public healthcare system, equipping them with the technical capacity to control and mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic was essential. According to the guidelines stipulated by India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), FLWs were to be trained on COVID-19 related activities.

Our study found that 99 per cent of FLWs were trained or received information on at least one COVID-19 related activity. Over 90 per cent had been trained on protecting themselves from contracting COVID-19, like training on the correct hand washing technique. Most felt that the training they received on these activities was adequate.

FLWs also collaborate with various government departments and each other to be able to carry out the full range of their tasks. For activities that required coordination such as managing stigma and discrimination around the disease, fewer FLWs had received training. Those who were trained on this component felt it was inadequate.

Figure 1:

Importantly, FLW trainings were conducted in-person before the pandemic. After the pandemic though, in-person trainings were held for around 50 per cent of Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) and ASHAs. Meanwhile, due to social distancing norms and travel restrictions, a majority of Anganwadi Workers (AWWs) were trained via WhatsApp or phone calls with their supervisors.

With the resumption of regular responsibilities – such as immunisation – by May 2020, FLWs had to adjust their ways of working to maintain COVID-19 precautions. Only 40 per cent of FLWs reported being trained on this component. Amongst those who did not receive this training, a majority felt that such training was not required, likely because they felt comfortable administering these activities while keeping precautions.

Insufficient Personal Protective Equipment

Ensuring continuation of health and nutrition services during the pandemic could only be accomplished by protecting FLWs from the risk of contracting COVID-19. Thus, furnishing FLWs with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) was crucial. Furthermore, FLWs saw an increased workload, had to travel longer distances, and had to take care of more people than usual. Therefore, resources such as mobile phones and transportation were also important.

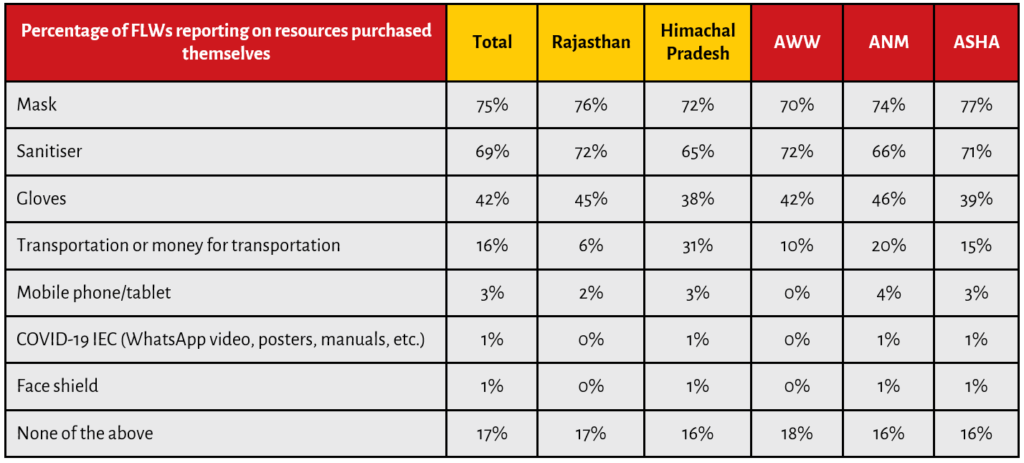

Despite directives by MoHFW stipulating the provision of PPE to healthcare workers, on-ground reports revealed a major scarcity of these necessary resources.

“There was a crisis of masks and sanitisers. I told my supervisor to provide them, but she told us that there is no supply from the Medical Department so buy them yourself.”

– ASHA, Jaipur district, Rajasthan

Of those surveyed in our study, all FLWs in Himachal Pradesh and 92 per cent FLWs in Rajasthan received at least one resource from the government (see Table 1 below). Masks remained the most widely received resource, followed by sanitisers, and gloves. Across the three FLW categories in the two states, AWWs reported having received fewer resources from the government, as compared to ANMs and ASHAs.

Also, despite the initial supply of resources from the government, a majority (83 per cent) of FLWs had to purchase or use their own masks and sanitisers. This was either because the quantity provided was insufficient or the quality was poor or both.

Table 1:

In fact, even as protective gear was not as readily available for them, citizens reached out to FLWs for PPE. However, 37 per cent of FLWs said that they were unable to comply with beneficiary requests, with 73 per cent citing lack of resources as the main reason behind this.

A shortage of resources, therefore, impacted their ability to effectively serve their communities.

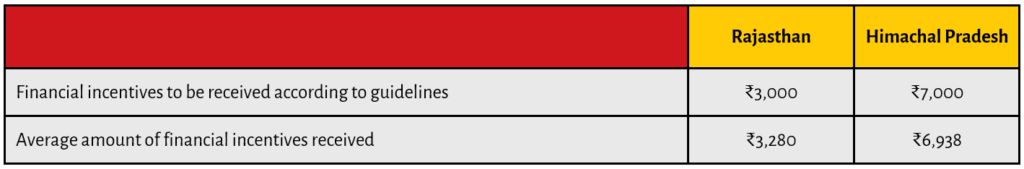

Incentives only announced for ASHAs

FLWs’ struggle on inadequate remuneration and irregular payments has been widely documented, and numerous studies have found that these impede their motivation to perform their duties.

In Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan, only ASHAs were provided monetary incentives for COVID-19 related work, and no such incentives were announced for AWWs or ANMs. The average payment received by ASHAs in Himachal Pradesh was almost twice the amount received by those in Rajasthan. On a positive note, most respondents reported receiving their incentive payments in a timely manner.

However, receiving adequate remuneration emerged as an important aspect affecting FLW motivation levels, as this was seen to be an important contributor to the overall household income. FLWs who felt inadequately compensated also felt demotivated. Even during the course of our survey, ASHA workers from Rajasthan went on strike due to inadequate payments.

Table 2:

Praise and public recognition for their work was low

Motivation could also be maintained and improved via non-financial incentives such as praise by supervisors and members of the government, or appreciation from members of the community. These have previously proven successful in motivating FLWs (Grant et al., 2018).

As with financial incentives, public recognition of their efforts during the pandemic was found to be low. Only 58 per cent of the interviewees mentioned being recognised for their contributions; this figure was higher for FLWs in Himachal Pradesh (73 per cent) than in Rajasthan (48 per cent). Mostly, recognition was in the form of praise by supervisors, followed by the provision of certificates, and praise by beneficiaries. Very few FLWs reported receiving recognition from government officials and politicians, in spite of public announcements made by the Union government applauding their work.

“My motivation is that this job is my only source of income. But during COVID-19 times, my motivation has changed because of how much people have started to appreciate me and my work… with applause, blessings. This keeps me going.”

– AWW, Jaipur district, Rajasthan

Motivation can be intrinsic as well. FLW recognition of their work’s value to the community can enhance their motivation and performance (Grant et al., 2018). In our study, some said they felt a sense of duty to help their communities and a sense of pride in having the knowledge to help community members. Some even discussed a sense of patriotic duty. These factors perhaps drove several FLWs to go above and beyond in fulfilling their responsibilities, and shouldering India’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, thus, FLWs were required to adapt to a new reality. While the government extended training and resource support to ease the transition, this was inadequate, as their experiences highlight. Their motivation too took a hit. Yet, this upheaval extended beyond the sphere of work as well.

Our next blog will explore the relationship between FLWs and their communities, and some of the challenges that they faced on a personal front.

Reference:

Grant, C. et al. (2018). ‘We pledge to improve the health of our entire community’: Improving health worker motivation and performance in Bihar, India through teamwork, recognition, and non-financial incentives. PLoS ONE, 13(8). Retrieved from URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0203265

This study was conducted through a research grant provided by Azim Premji University, as a part of their COVID-19 Research Funding Programme 2020.

Download Data Visualisation: Health and Nutrition Services during COVID-19

Also Read: ‘People Thought of Us As Virus Carriers’