This blog is part of a series. The first blog can be found here.

In my previous blog, I explored petty and grand corruption in the health sector. In this blog, I look at the main causes of corruption in the sector which arise from the following:

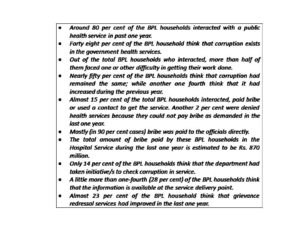

First, there is a lack of useful information available to users of the health protection system. In many health institutions, there is lack of information on what services are provided, where and when they are provided, who provides them and the procedures to be followed. This creates an environment for soliciting and paying bribes and also tempts many lower and middle level staff to turn into middlemen and accept a cut for making such services available.

Second, there is excessive red tape, understaffing and therefore, long queues. Some processes and procedures, even if they are necessary, can result in long queues if there are shortages and inefficiency. This again leads to speed money bribes for jumping queues. This again arises due to unrestricted influx of patients to government hospitals and a weakly functioning referral system (even if it exists on paper) within the government health care hierarchy of institutions.

Third, shortage of medicines and other medical supplies results in long waiting lists, including for elective services like surgical operations. Bribes are collected for jumping the queue. Sometimes, shortages can force hospitals to only perform emergency operations, leading to a higher premia for queue jumping.

Fourth, comparatively poor salaries might lead health workers (including doctors) to take bribes. One way to overcome this is to allow doctors to engage in private medical practice after their official hours of service, so that they can increase their income even when retained in Government Service. However, this move has had some negative consequences, as follows:

- Doctors spending official hours in their private clinics, whilst absenting themselves from government hospitals, leaving patients unattended.

- Doctors using government facilities and medical supplies to treat their private patients on priority basis.

- Doctors using public facilities as a conduit to channel clients to their private facilities.

- Doctors prescribing medicines that they know are not available in government facilities, and advising patients to procure them from their private facilities.

- Theft and pilferage of medicines, equipment and consumables from public health facilities.

Fifth, poor management and supervision of health workers leaves them unchecked to do whatever they want to do. This leads to a breakdown of the management structure within a health institution. For example, the head of the institution may hesitate to take action against a junior staffer, who becomes more influential due to closeness to a powerful politician or bureaucrat (doctors who treat VIP patients are often treated leniently by their politically powerful patients). These become poor examples of good management for junior staff and more doctors attempting to build their influence through cultivating rich, famous and politically influential patients.

Sometimes, institutions that are designed for improving management, themselves become institutions of exploitation and corruption. For instance, local politicians and newly constituted local advisory bodies have the potential of improving the management of institutions. Instead, they often increase mismanagement by using their influence and power to seek individual favours. Sometimes, they build unholy alliances with corrupt interests and increase, rather than decrease the prevalence of unethical and corrupt practices at all levels. The media, through their potential for undertaking sting operations, can become institutions of exploitation and extortion too.

Unionisation of staff can lead to arm-twisting of hospital managers, unprofessional behaviour and mafia style running of corrupt syndicates that can powerfully resist reforms. They can also influence postings and transfers of senior managers.

Sixth, some kinds of corruption arise out of disregard of the law and/or its intentional breach. In many such cases, there is also collusion from the public and therefore, rarely do such instances come to light. Examples are as follows:

- Pre natal sex determination tests;

- Submission of false post-mortem reports, or doctors looking the other way, when the police falsify dying declarations in the case of victims of dowry related offences;

- Trading in organs for transplantation;

- Undertaking tests of medicines on patients, without authorisation or their consent. Sometimes, these battery of unnecessary tests are made expensive in the name of doctors giving themselves protection against accusations of negligent treatment later on.

In my next blog, I discuss various strategies for the reduction and hopefully, the elimination of corruption in the health sector.

Also Read: How the Lack of Information Can Affect Health Insurance Schemes