Menstrual Health Services in India: A Comprehensive Overview of the Public System

2 September 2022

Menstrual health is defined as the state of “complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing” during menstruation. Existence of commensurate sanitation and water facilities, access to period products and disposal systems, valid information channels, and community participation comprise the comprehensive set of services that promote and enable menstrual health. This is the first blog of a two-part series that explores the current landscape of public service delivery and some challenges in realising menstrual health in India.

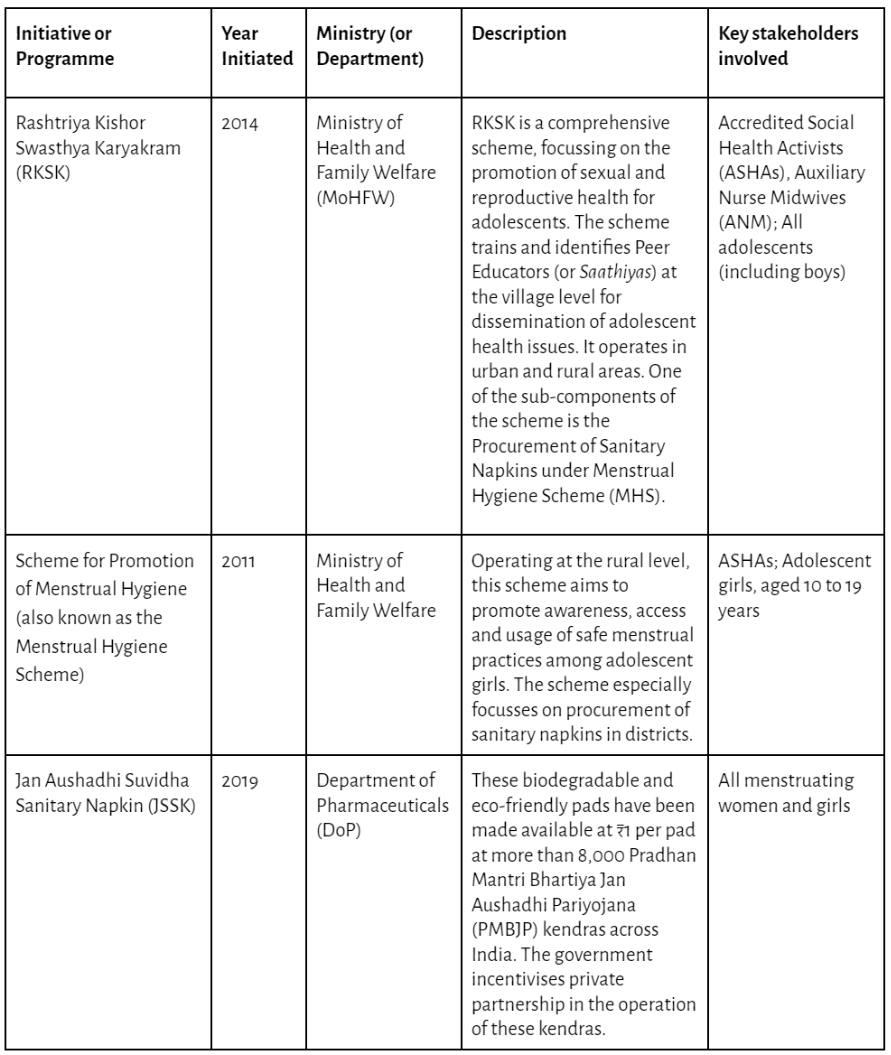

Menstrual health services in India are provided at the level of Union, state, and local governments. At the Union level, menstrual health is actualised through three key initiatives (Table 1).

Table 1: Initiatives Providing Menstrual Health Services in India

MHS and RKSK are a part of adolescent health programmes under MoHFW’s key centrally sponsored scheme — the National Health Mission (NHM) [1]. Operationally, MHS is also a part of RKSK’s community-based approaches. Under this initiative, adolescent girls are eligible to receive a packet of six sanitary napkins (or pads) for ₹1 per napkin. These napkins may be distributed at schools, Anganwadi centres, or through door-to-door visits by health workers.

Another scheme that distributes sanitary napkins is a part of DoP’s central sector scheme [2] of PMBJP called the JSSK. Popularly known as the Suvidha scheme, over 273 lakh sanitary napkins were distributed in 2019-20, increasing to 1,128 lakh by 2021-22.

Additionally, apart from the key initiatives mentioned in Table 1, the recent guidelines for Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 of the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) suggest convergence with MoHFW’s existing menstrual hygiene programmes. Under its component of Scheme for Adolescent Girls, the guidelines indicate the “promotion” of menstrual hygiene [3].

Thus, while some components within the schemes and sub-schemes focus on awareness generation on menstrual health, public intervention mainly focusses on the distribution of sanitary napkins.

Looking at the state level, yet again, service delivery prioritises the availability of sanitary napkins. Several states such as Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, Sikkim, and Uttar Pradesh have made an attempt to distribute sanitary napkins. Under their distribution strategy, school-going adolescent girls are especially targeted because not only are over 71 per cent of girls unaware about menstruation till their first period, several drop out of school soon after.

There are several ways in which menstrual services are delivered at the state level.

In 2018, Maharashtra initiated the Asmita Yojana under its Department of Rural Development. Under this scheme, SHGs procure sanitary napkins from suppliers and register on a mobile application, and distribute them to Asmita cardholders, mainly school-going adolescent girls, at ₹5 per pack. During the World Menstrual Hygiene Day 2022, the government announced another scheme for the distribution of sanitary napkins, priced at ₹1 per 10 pads, to women in below-poverty line (BPL) households and those engaged in self-help groups (SHGs) in rural areas.

Operating under the aegis of Rajasthan’s Department of Women and Child Development (WCD), the state has attempted to make sanitary napkins free-of-cost for all women and girls through its Udaan scheme. Schools, colleges and Anganwadi centres distribute these napkins. Similarly, Andhra Pradesh provides free sanitary napkins through its WCD’s Swechha programme; however, the scheme is restricted to school-going adolescent girls.

Some path breaking initiatives have also been realised at the grassroots.

In 2021, Raigarh district in Chhattisgarh initiated Pavna, a community-led menstrual hygiene programme. The programme includes training and supporting SHG members to produce and distribute pads through village markets; and convergence with other schemes and departments, such as the Rurban mission and Department of Education. Through its “whole-of-society” approach, it facilitated the breaking of social taboos in remote areas, while simultaneously increasing the usage of sanitary pads from 40 per cent to 75 per cent within a year.

Marking another feat, this year, a village in Kerala stepped up to distribute over 5,000 menstrual cups – a sustainable alternative to sanitary napkins – to women over 18 years. Like Kerala, recently, a Gram Panchayat in Karnataka also distributed 2,300 menstrual cups to women and girls in the community.

Through these various initiatives, menstrual hygiene has improved. According to India’s National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-V (2019-21), 73 per cent of rural women aged 15 to 24 years use hygienic methods of menstrual protection, up from 48 per cent in NFHS-IV (2015-16).

However, despite strides in the delivery of menstrual health services in India especially at the sub-national level, challenges remain in the usage of services by menstruators. Most of these challenges are interrelated.

In India, cloth-use is still widely prevalent, with 50 per cent menstruators exhausting this option after sanitary napkins (64 per cent). Further, focussing on one kind of period product promotes a one-size-fits all approach, deprioritising comfort and safety of menstruators. Under Maharashtra’s Asmita Yojana, for example, sanitary napkins were found to be unusable because of their low quality — non-absorbent capacity and small size. This also points to an unrealised gap in using other and more sustainable alternatives to sanitary napkins [4].

Moreover, schools have been the mainstay of distributing sanitary napkins in rural areas. With school closures during the pandemic-induced lockdowns and an inability to afford sanitary napkins at market prices, girls have resorted to using unsanitary cloth during their menstrual cycle. This negates the partial gains made on hygienic menstrual practices too.

Education levels and household wealth characteristics add another layer of complication to women’s use of hygienic menstrual methods in India. According to NFHS-V, women belonging to the wealthiest households and holding a high school education are twice as likely than those in the least wealthy households and without a school education to practise hygienic menstrual methods.

The next blog will dive into menstrual hygiene awareness and some other challenges in realising menstrual health in India.

Tanya Rana is a Research Associate at Accountability Initiative.

Also Read: Under-prioritisation of Women’s Safety in the Union Budget?

Notes

[1] Adolescent health is a sub-component of NHM’s Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) component.

[2] A central sector scheme receives 100 percent funding assistance from the Union. Funding for a CSS is divided between the Union and states, usually in the share of 60:40, with the Union plugging in the major amount of this share.

[3] Menstrual hygiene is a “non-nutrition” component.

[4] According to NFHS-V, only 0.3 per cent and 1.65 per cent of women and girls between the age of 15 to 24 years use menstrual cups and tampons, respectively, in India.

One thought on “Menstrual Health Services in India: A Comprehensive Overview of the Public System”