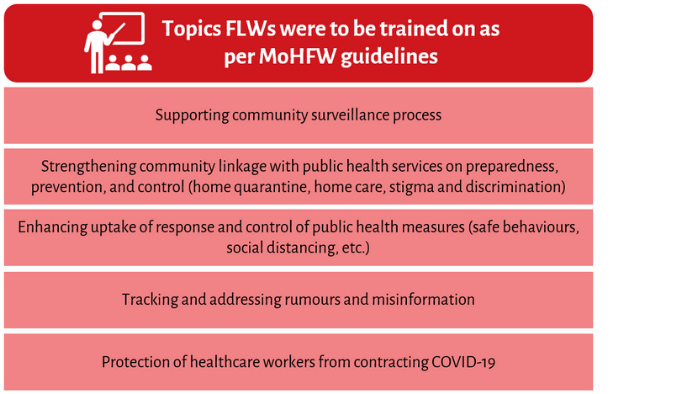

For Frontline Workers (Anganwadi Workers, ASHAs, and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives), increased responsibilities and having to juggle different tasks were not their only priorities. Behind the scenes, they have often struggled with challenges in their communities, and personal and familial lives in the last year.

We conducted a study in two districts of Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan from November 2020-January 2021 in order to understand the experiences of Frontline Workers (FLWs) and their new challenges arising from the pandemic. (The report is available for download from here.)

FLWs reported facing backlash from community members

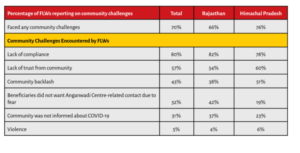

In our survey, 70 per cent of the respondents faced community-related challenges. The lack of COVID-19 appropriate behaviour by community members, and a lack of trust on FLWs were the most-widely reported hindrances.

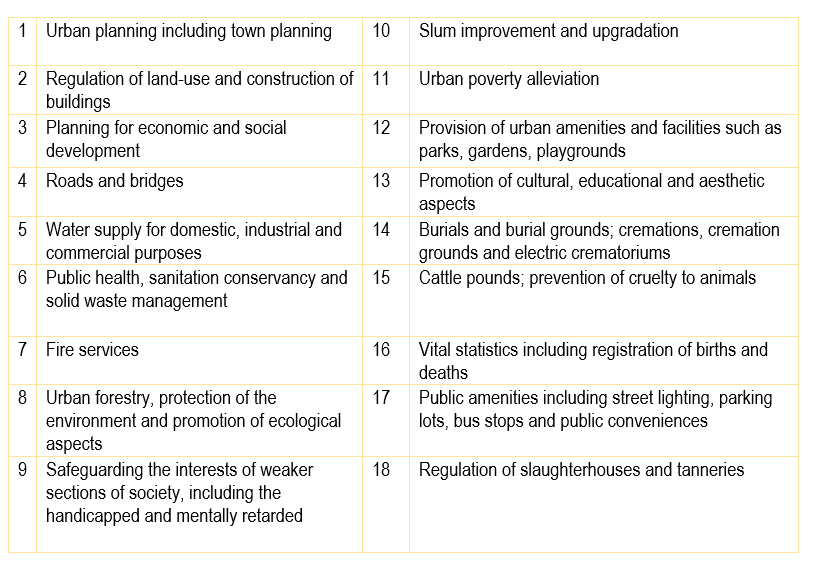

Almost half of the FLWs surveyed also reported facing community backlash. This manifested through verbal abuse, refusal to allow FLWs into their homes, refusal to cooperate with COVID-19 protocols and, in more extreme instances, physical violence (refer to the Table below).

Insights from qualitative interviews shed more light on the reprisals, which could be attributed to the prevalence of a fear of contracting the COVID-19 virus, frustration about multiple household surveys and testing, and some instances of returning migrants refusing to quarantine.

Worryingly, 5 per cent of FLWs also reported facing violence, in part, arising from fears that FLWs could be ‘virus carriers’ and would spread the disease. But FLWs had little option and had to go into the communities. Given the increase in workload and the number of villages covered, FLWs often had to travel long distances late at night which also raised issues surrounding their safety .

“Once, while doing door-to-door surveys, some men passed comments and said bad things about my work and my character. It was late in the evening so I was scared and reached out to the police for help. They handled it by talking to those men.”

– ASHA, Kangra district, Himachal Pradesh

On the other hand, there were also instances of positive interactions between the FLWs and their communities. This was particularly true for FLWs who had been working with their communities for many years, and also for FLWs working in their own villages, where they had a strong working relationship with the community.

FLWs were affected with a loss in household income during lockdown

With the strict nationwide lockdown introduced to curb the spread of COVID-19 in 2020, people all over India grappled with the shutting down of businesses, job losses, travel restrictions, and being unable to meet friends and family. FLWs were no exception. Sixty-nine per cent of the FLWs said that they faced at least one of these challenges during the lockdown.

Multiple polls and surveys during the lockdown revealed that, despite both partners working, the burden of household chores and childcare fell unevenly on women, more than men. This was also the case for the FLWs – 30 per cent reported that they faced the challenge of balancing their workload additionally with household duties.

Another widely mentioned challenge was that of unemployment. India’s monthly unemployment rate increased to 23.5 per cent in April 2020, up from 8.7 per cent in March. Thirty-five per cent of FLWs in Rajasthan and 19 per cent in Himachal Pradesh reported that either family members faced unemployment or their household experienced a loss of income during the lockdown.

Most FLWs were anxious about falling sick and infecting families

Alongside these household challenges, we enquired about personal challenges faced by FLWs – 67 per cent responded facing such challenges, primarily the fear that they or their family members could fall sick. These fears were legitimate – FLWs were involved with surveillance of community members suspected of showing COVID-19 symptoms during and after the lockdown. Moreover, around 30 per cent also reported that their family members did not want them in the same household for fear of contracting the virus.

Thus, FLWs faced multiple pressures in carrying out their jobs.

This is the third blog of a series. The first blog can be found here, and the second blog is available here.

This study was conducted through a research grant provided by Azim Premji University, as a part of their COVID-19 Research Funding Programme 2020.

Download Data Visualisation: Health and Nutrition Services during COVID-19